It’s great to see my review of Denise Nadeau’s book Unsettling Spirit: A Journey into Decolonization in the most recent issue of Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses. SR is not an open-access journal, so if you’re interested in the full review, you can find it through your local university library (perhaps). If that’s not an option, DM me!

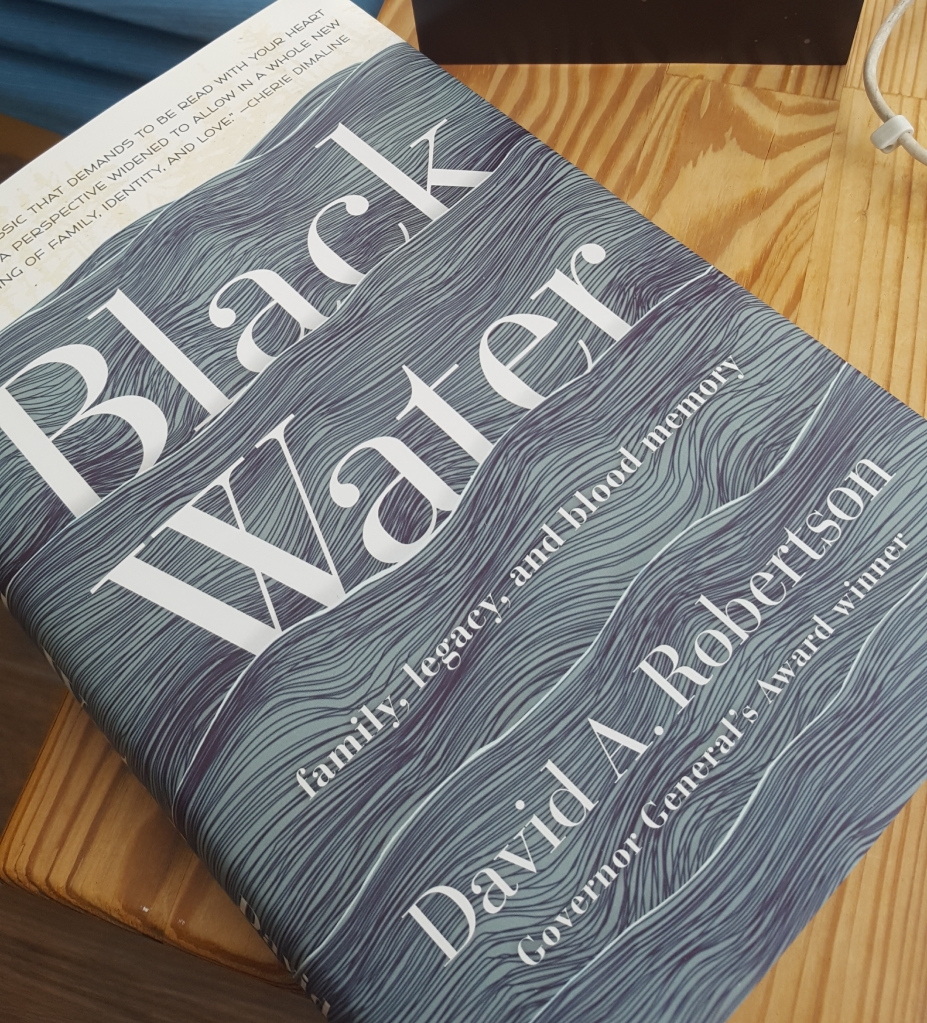

Nadeau’s book is a good example of a growing field of writing by Canadians, Americans, Australians, New Zealanders, and South Africans, which self-reflexively thinks about their histories and actions in relation to Indigenous populations. Writing by these groups, which is aimed at other folks within that group (people like me) has been called “settler colonial” literature. I also call it “aware-settler” writing. Some folks, including many Canadians who are willing to accept that there have been, and continue to be, injustices, don’t like the term settler. While it’s true that it was my grandfather – not me – who homesteaded in SW Saskatchewan, and that he was the first “settler” in my family, as a Canadian I still benefit from the ongoing appropriation of Indigenous Land. So does my government. So do resource companies granted rights to exploit those lands. Calling ourselves settler reminds us that the expropriation and injustice don’t just exist in the past.

I hope you’ll read the review. And the book! Nadeau does a wonderful job of telling her own story (situating herself), naming her relations (the Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons from whom she’s learned), and passing on some of the wisdom she’s gained (bringing good back to the community). These are actions we’ve learned from Indigenous writers, and from which we all gain. Nadeau’s book is published by McGill-Queen’s Press.

Ultimately, the point of aware-settler, or settler-colonial, writing is most often just to remind those of us who are not Indigenous of our obligations. Surely no responsible person can take issue with, well, actually taking responsibility.