If you only read the first line of this blogpost, here’s the message: read this book. If you can, buy it.

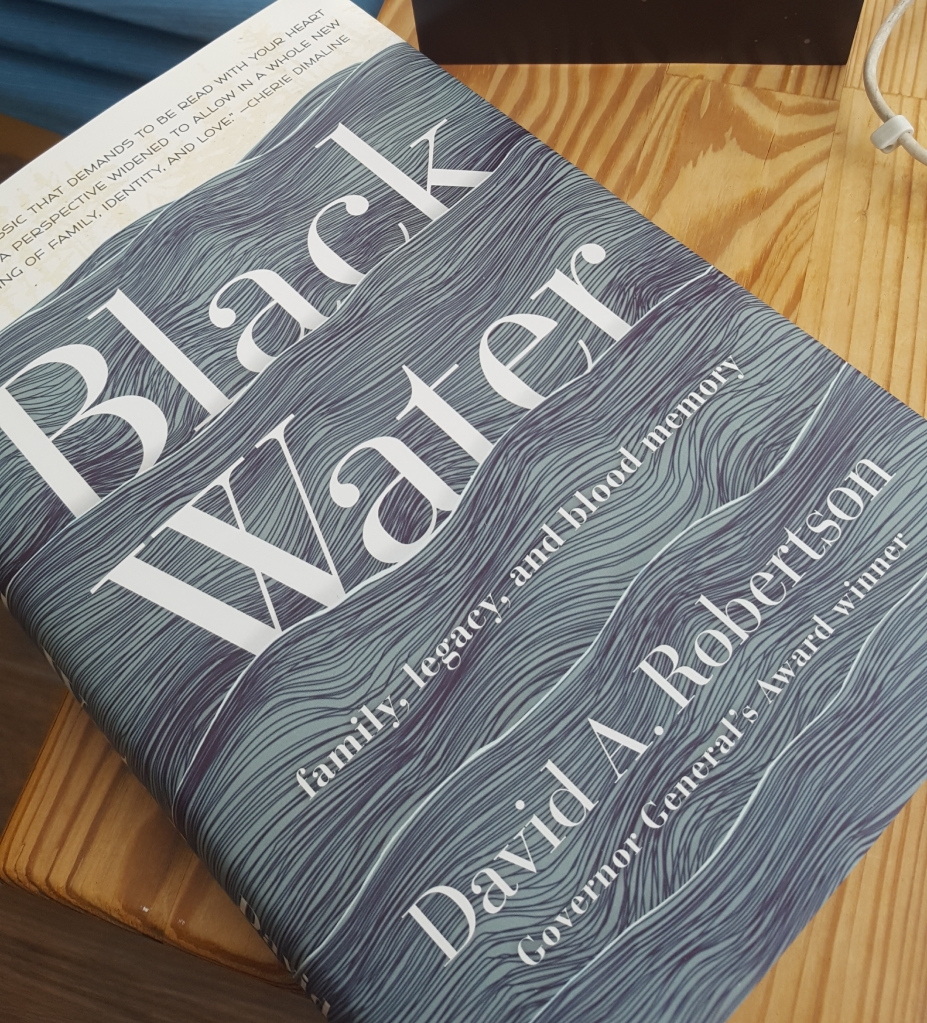

By purchasing and reading Black Water you’ll not only grow yourself. You will also support an honest, warm, thoughtful, skilled, and open-hearted writer. You’ll be amplifying an important story, not just the one David A. Robertson tells about his identity, his family, and his father, but the narratives within which this memoir is nestled.

Black Water starts with the word “Dad.” David’s Dad – his presence, his absence, his words and his silences – fill its pages. Since father-son stories are hardly unusual (think Star Wars, Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, TV’s Brooklyn 99) what makes this book so compelling is not just Robertson’s craft, but the particular heritage that Donald Alexander Robertson, Dulas to his friends and community at Norway House Nation, embodied. Dulas was Cree (Robertson tends not to use the word nêhiyaw). So is David. Yet as he writes, “Mom and Dad never told me that I was Indigenous when I was a kid, and because of that, I grew up disconnected…”

Coming of age stories are often about finally making the connections and finding the pieces that help us recognize ourselves. David’s takes place first in rural Manitoba and in Winnipeg. He grew up fitting in, in many ways, and markedly not fitting in, in others. As a bookish nerd raised in Saskatchewan, I could empathize with many of David’s struggles. This is Robertson’s fine writing: his story is incredibly personal and particular, but he tells it in ways that make it universal.

Whether Cree or other First Nation, many Indigenous writers emphasize the importance of both relationship and specific Land to our identity. This is where the book’s name – Black Water – comes in. Black Water is the northern trapline where Dulas grew up. Dulas tells David he wants to visit the community, and the place, one last time. Robertson writes his memoir around the journey with his father to Black Water. Into this final journey he weaves stories of his own children, his brothers, and his father, and how all of them have learned to relate to this special place. As someone who writes about, studies, and walks, pilgrimages, I could see so many elements of pilgrimage in their voyage.

There’s nothing teacherly or preacherly about this book, at all. It simply tells David Robertson’s story, a story that includes golf and vegetarianism as much as trap-lines and residential schools. Like all good family stories, it’s complicated. Parents don’t always understand kids. Kids, even when they become adults, never seem to learn the full truth about their parents. In the midst of those common narratives, and so gently we hardly realize it, we learn some of how Indigenous peoples have been forcibly disconnected from their land, and the assimilative pressures – sometimes unconscious, often more racist – brought to bear by Canadian society. We also learn of the various ways Indigenous connections between identity and Land are being reforged despite these pressures, and new identities established.

Black Water isn’t a textbook. It’s a quiet, personal, unassuming son’s story of how he grew up. The great thing about this book, and the reason those of us who are not Indigenous should read it, is that if enough of us do so, our whole society can learn something about growing up with him.