There’s a fascinating myth, from a time long before the New Testament, about the most famous of the Greek heroes, a half-man, half-god known as Heracles. Heracles is the hero we usually know by his Roman name, Hercules. There must be a hundred tales about Hercules and his exploits and combats and loves. But Isaiah 40 makes me think of one where Hercules meets a Libyan named Antaeus. Antaeus is a giant, and a terrible monster. Every passer-by he challenges to a wrestling match. And every wrestling match he wins. And then Antaeus kills those passers-by and uses their skulls to build a temple to his father, Poseiden. No one travels anymore. The giant has terrified and desolated the whole area.

Hercules meets Antaeus when he is forced to go past him on one of his quests. Antaeus, as usual, challenges the traveler to a wrestling match. Hercules, never one to shy away from combat, of course says yes. Antaeus is a giant. But Hercules is….well, he’s Hercules.

Unfortunately, despite that, the wrestling match doesn’t go well for Hercules. Strong as the hero is, every time he throws Antaeus to the ground, the giant only heals and becomes stronger. In fact, every time Hercules throws him down he comes back twice as fast and twice as tough. Something is terribly wrong.

As the Greeks tell the story, it’s only at the last minute, only just as he’s about to die of exhaustion and from the beating he’s getting, that Hercules realizes the giant’s secret. Antaeus takes his strength from the earth. Hercules realizes that so long as he’s in contact with the earth, Antaeus cannot be beaten. So then Hercules shows that he is a hero not just in brawn, but also in brains. He lifts the giant up from the ground and holds him away from the soil and hugs him in a terrible bear hug. Try as he might, the giant Antaeus cannot reach the ground. And so Hercules finally crushes him, and frees the country, and saves his life.

In this story, it’s actually the giant I identify with, not the hero. We hear, more and more, that we’re the first generation so completely disconnected from the real world. Where is the earth, for us? We’ve covered our planet in so much concrete, and spend so much time indoors, and so often we go straight from work to car to shop to house, that we don’t feel that vital connection to the environment that we need. I know some Finns who actually had their neighbors call the police when they saw them put their baby in a stroller and leave them outside. Outside is considered dangerous in our country! The younger we are, the worse it is, with our heads in screens or on smart phones or working in cubicles or texting. Too often we don’t feel that connection from which, like Antaeus, we gain our strength.

Have you not known? Asks Isaiah. Have you not heard? Has it not been told you from the beginning? It is the Lord who sits above the circle of the earth, who stretches out the heavens like a curtain, and spreads them like a tent to live in, who brings princes to naught and makes the rulers of the earth as if they were nothing.

And apparently, ONLY the Lord. A lot of our problems in this world arise from the fact that we human beings have ignored the fact that we’re NOT gods. We’re not above the natural world – we’re PART of it. We’re not above time, we’re IN time. And we’re learning more and more every year that we’re certainly not above our bodies. We’re not above the muscles, bones, organs and skin that make us up. We are – every single one of us – finite and physical. And so we need things: we need rest. We need renewal. And we need connection.

Isaiah 40 is one of the strongest reminders in scripture of who we are, and of exactly what connection we need. Have you not known? asks Isaiah. Have you not heard? The Lord is the everlasting God, who does not faint or grow weary.

Believe it or not the point here is not just about a deity. By drawing such a strong image of God, Isaiah is showing us what we human beings are NOT. Even the most powerful among us can be brought low by a cold, an infection, old age, or a tragedy. Our riches ultimately mean nothing. Our accomplishments will fade. As Isaiah writes Scarcely are they planted, scarcely sown, scarcely has their stem taken root in the earth, when God blows upon them, and they wither, and the tempest carries them off like stubble.

I don’t know if you’ve seen images of the massive snowfall in New Brunswick this week. There’s been something like – what is it? Four FEET of snow that’s fallen. They’ve been shoveling all week. There’s a video going around that some guy took on his cell phone of a train coming down the track near Moncton. It’s hilarious. You can’t even SEE the train at times, through all the snow that it’s pushing out of its way.

That’s the truth about the world, and about us. We’re in a world that is part of us, and from which we cannot and should not escape. Winter has a way of reminding us – we human beings are not so high and mighty as we sometimes think. We’ve spent so many years thinking we’re NOT part of the created order that we’ve fouled our own homes. The environmental crisis shows it. Imagine if Isaiah had known about asthma, childhood obesity, rising rates of cancers and the epidemic of measles and other diseases caused by the fact that, stupidly, we know about vaccinations but don’t use them: Even youths will faint and be weary, and the young will fall exhausted.

In perhaps the most ironic twist of all, we’ve also separated any faith we have from our creatureliness. We’ve acted, even in the church, as if God and creation were separate. Paul writes, in Romans: The creation itself waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God. According to the apostle, the world, like us, is part of this grand interconnectedness of all things, this sin and rebellion and redemption cycle. Creator-creation-creation-creature. We and our Creator and the earth that we are part of, all belong together. And only together can we connect with the strength of that earth, of being “created good”.

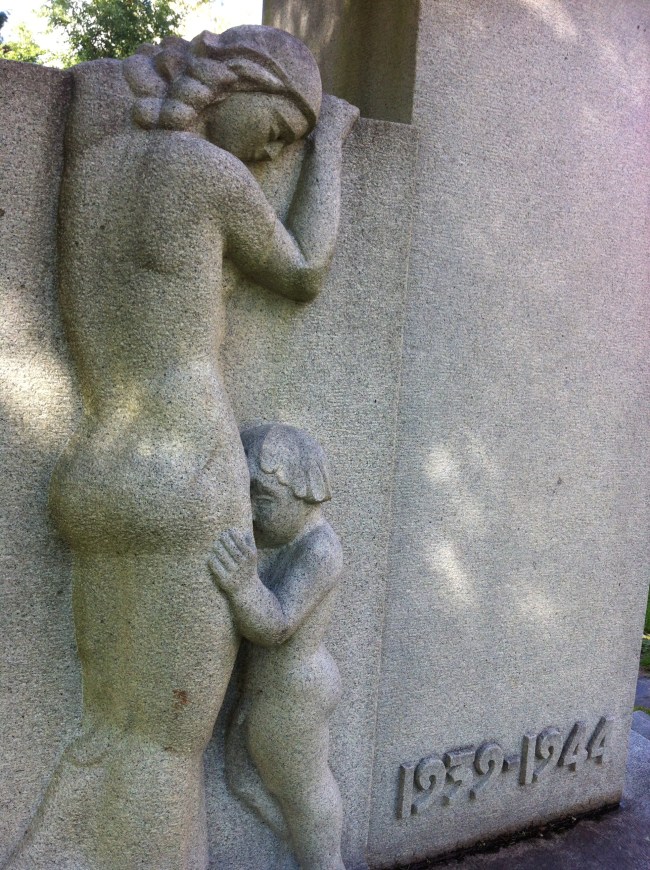

When we go to a funeral we hear these words: “we are dust, and to dust we shall return”. That giant, Antaeus, knew that it was the dust that made him strong. We too take our strength from being part of the creation where God has placed us. The more we realize that, the more we will allow ourselves actually to BE creatures. We’ll allow ourselves to admit that we have needs. We will allow ourselves to admit that in fact, suffering and pain, too, are a natural part of life. And the strange thing is, if we can really be weak, then oddly enough, we will be stronger for it.

God gives power to the faint. Those are the words of Isaiah. The powerless can and will be strengthened. He goes on to say: Those who wait for the Lord shall renew their strength. They shall mount up with wings, like eagles. They shall run, and not be weary. They shall walk, and not faint.

This is what our faith tells us. Hercules is a fine hero, and Antaeus a villain. But I understand my faith, not through the hero, but through the vanquished giant. Like him, we NEED the earth. Like him, when we remember where we come from, when we stay in touch and don’t let ourselves be isolated, from the earth AND from the One who created it, we will be the stronger for it.

Have you not known? Have you not heard? asks Isaiah. Wait on the Lord and renew your strength. God is faithful. May we learn to rely on that faithfulness, and from that faithful Creator, in our world, take our strength.