I wasn’t expecting to like “The Everlasting People.” I hadn’t heard of the book, and hadn’t asked to review it. When the review editor for the Oxford journal Literature and Theology, Alana Vincent (now an Associate Professor at Umeå University), asked me if I’d be interested, my first reaction was to go into that quick calculation academics do, of whether a free book will be worth the work.

Turns out it was. The reason I’m calling this “Misjudging Milliner” was because that’s exactly what I was guilty of. Traumatized by the previous American president’s and administration’s links to certain churches, and by the ongoing efforts of many American so-called Christians who seem to be doing everything right now NOT to love their neighbours and practice justice, it seemed from the get-go that a book aimed at evangelicals would definitely not be one I’d like. As a settler trying to do my bit for more justice and for Treaty respect in relations with Indigenous peoples, I was pretty sure the book would be more cringe- than compliment-worthy.

I was wrong.

Milliner has gone through the hard work of learning about the First Nations of Turtle Island. He has developed relations, listened more than spoke, and learned at the feet of his Indigenous mentors.

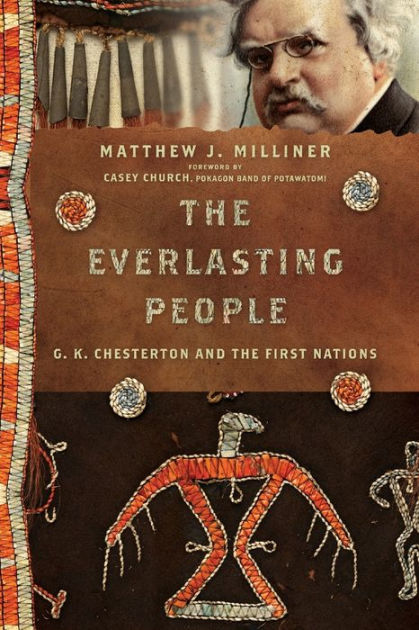

G.K. Chesterton, who features on the book’s cover, is a bit of an excuse for Milliner to grab his non-Indigenous, evangelical audience (whom he is presuming like Chesterton) and keep their attention long enough to teach them a bit about the Land where they actually live – and not early 20th-century England, where they do not. I applaud this aim.

In the places where the book presumed a U.S. audience or made references to the “insider language” or experiences of evangelicalism, I still occasionally found it grating. However, I was not the target audience, and there were fewer such moments than I’d assumed.

There was much to learn in the book. I especially appreciated the example of someone who takes the time to learn the Indigenous history and culture of where they live and work. Mid-western Americans especially, but non-Indigenous North Americans in general, will appreciate Milliner’s journey, and the illustrations he uses. All of us who are non-Indigenous and living in North America should be on the journey Matthew Milliner is taking.

Oxford Press has made it possible for me to share the book review (normally it’s behind a paywall). You can find the link here in case you’d like to read it!